-

Maybe It's Time 5:190:00/5:19

-

The Great Plains 5:500:00/5:50

-

Nantucket Sound 4:450:00/4:45

-

Prime Meridian 5:120:00/5:12

-

Philadelphia, 1918 5:280:00/5:28

-

0:00/2:39

-

World On Fire 3:040:00/3:04

-

Peace River 5:310:00/5:31

-

Wax Anvil 5:460:00/5:46

-

0:00/5:04

-

Dodger 4:590:00/4:59

-

Unwritten Story 4:080:00/4:08

The Story

The Fields of Gettysburg is based upon actual events that took place at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on July 1 - 4, 1863. The characters of "The FOG" are also based upon real people.

During the weeks leading up to July 1st, the Confederate's Army of Northern Virginia, led by General Robert E. Lee, pushed its way northward into south-central Pennsylvania. General Lee intended to attack and crush the Union's Army of the Potomac in the North. If successful, the Union would surely be demoralized; and then, perhaps psychologically weakened to the point of capitulation.

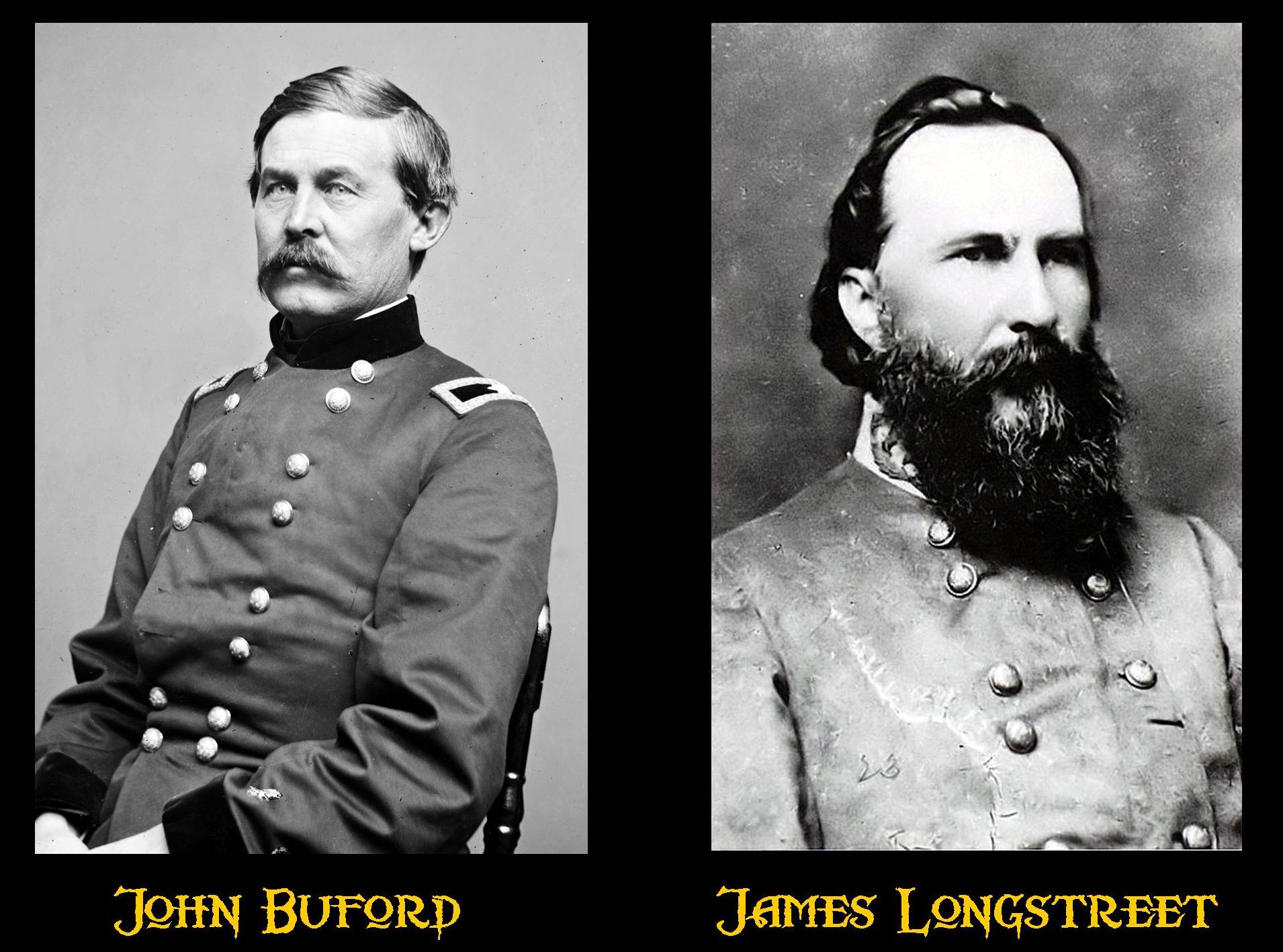

On the morning of July 1st, Brigadier General John Buford surveyed the west from the cupola of the Lutheran Seminary. He commanded the 1st Cavalry Division, the first Union force on the scene at Gettysburg. Actually, in the early hours of that first day, Buford's Division was the only Union presence on the scene as he began to understand the inestimable threat approaching from the west down Chambersburg Pike (a.k.a., the Cashtown Road). John Buford astutely assessed the lay of the land and anticipated the flow of the ensuing conflict. Buford positioned his men and assets in a configuration to delay the influx of Confederate forces into Gettysburg. His insightful and decisive actions provided the Army of the Potomac the opportunity to concentrate its forces at Gettysburg and occupy the high grounds of the Cemetery Ridge. This strategically advantageous position would ultimately prove to be unbreakable.

John Buford was, by all accounts, a dutiful and determined U.S. Army officer. A West Point graduate and veteran of the Indian Wars, the Utah War, and the peacekeeping forces during the Bleeding Kansas confrontation, Buford was no stranger to hard travel and even harder duty. Regarded as one of the finest Cavalrymen in American Military history, Buford - largely in the saddle of his trusted mount, Grey Eagle - General Buford gained legend as an expert horseman.

In addition to being a innovative battlefield tactician with a keen eye for overall theater of battle, General Buford was intensely loyal to the U.S. Army and the United States. As the southern states began seceding, the Kentucky born Buford was sought after by the South to assume a leadership position in the Confederate Army. He declined, reaffirming his dedication to his country. John Buford was no-nonsense and had seemingly limitless energy to press on relentlessly. He was a "roll your sleeves up" kind of leader, never expecting his men to do what he wouldn't do himself. General Buford gave everything he had to give.

On the Confederate side of the field, Lieutenant General James Longstreet, was second in command to Robert E. Lee at Gettysburg. Lee described Longstreet as "the staff in my right hand." Longstreet had a well-deserved reputation as a fearless, hard hitter. He was commonly observed sitting tall in the saddle of his beloved warhorse, Hero, at the front, inspiring his men as they poured into the fray. Like Buford, Longstreet was a skilled equestrian. A West Point graduate as well, General Longstreet came to Gettysburg with twenty years of service as an officer in both the U.S. and Confederate Armies, including combat experience in the Mexican-American War.

Prior to 1863, General Longstreet endured tremendous personal tragedy, burying five of his children; three of those five children perished within one week in the winter of 1862 from scarlet fever. This experience darkened Longstreet's spirit -- more so than the abundance of the death and depravity of war surrounding him. Perhaps his personal situation influenced his leadership style at Gettysburg; his actions during these historic days have been debated - often hotly - ever since. History is clear that General Longstreet did not agree with General Lee's plan of attack and was quite vocal about his misgivings.

View from "The Angle" towards the Codori Farm. This serene field of Gettysburg is the site of Longstreet's fateful attack of the Union's center, better known as "Pickett's Charge." General Lee's plan to demoralize the Union backfired here as a result of the carrying out of his audacious battle plan.

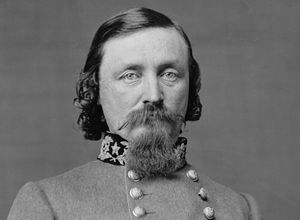

General Longstreet, after voicing his disagreement to General Lee, ultimately followed his commander's orders. Then, as James Longstreet feared, the results of going on the offensive were finally disastrous for the Army of Northern Virginia. On July 3rd, the Confederate plan of attack imploded when General George Pickett's Division charged across the seemingly endless open field toward "the Angle" on Cemetery Ridge only to be decimated. Did Longstreet's apprehensions delay his maneuvers on the field? If so, did these delays fulfill his premonitions of failure? Or, was Longstreet simply dead-on with his assessment of General Lee's headstrong strategy?

General George Pickett

The debate on Longstreet's performance at Gettysburg has endured since the battle occurred. No doubt, the Lieutenant General exhibited plenty of uncharacteristic behavior during those first three days of July. However, he was also burdened - perhaps more so than any other senior commander under Lee or Meade - with the responsibility for executing bold battle plans on the backs of tens of thousands of men. Surely, Longstreet's lack of faith in those plans and his legitimate concern for the welfare of those thousands of men impacted his battlefield thought process and subsequent actions. If anyone was deeply conflicted at Gettysburg, it was James Longstreet.

Innocence Lost

In the 1860's, Gettysburg was a town of about 2,500 inhabitants. Then and today, a map view of Gettysburg resembles a wagon wheel - the town at the hub with several primary roads that spoke out from the burg's periphery. This characteristic undoubtedly drew the opposing forces into the fields, hills and woods of the town; converting it into a terrible theater of war. Prior to those fateful days in early July, 1863, Gettysburg's main street bustled with the businesses and trade of the day; the farm fields brought forth wheat, corn, fruit orchards, and cattle; and the folk of Adams County raised their families in due course.

Gettysburg was the epitome of small town America after the American Revolution. After the great battle of 1863, Gettysburg would be forever changed.

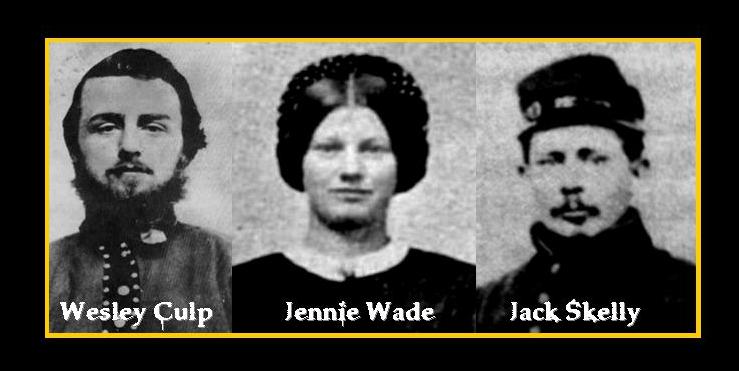

For three young friends who hailed from Gettysburg, the war would prevent them all from growing old together, or apart.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the young men of America's communities were drafted into service, typically to serve in the militias of their home state. This was true for Johnston "Jack" Skelly. Young men from Adams County were called up to serve in the 87th Pennsylvania Infantry regiment on a three year enlistment.

Jack's boyhood friend, Wesley Culp, would have been mustered into the same regiment; but young Culp had moved to Shepherdstown, Virginia (part of West Virginia since 1863) in 1858 to follow his trade as a harness maker. When the war broke out in 1861, Culp chose to join the Confederates as a Virginian. He enlisted with the 2nd Virginia Infantry regiment - a component of the famous "Stonewall Brigade," led by Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson himself until his death in May, 1863. Culp's own brother, William, was a soldier of the 87th Pennsylvania along side Skelly. Wesley Culp's decision to stay in the South and become a Confederate soldier made him the object of scorn in his hometown. His brother disowned Wesley as a traitor and never spoke to him or of him again.

Jennie Wade, also a friend of Wesley Culp from childhood, was engaged to Jack Skelly when the war broke out. Jennie was 20 years old in 1863, and worked as a seamstress with her mother, Mary, with whom she lived. As the conflict approached the streets of Gettysburg, Jennie and her two younger brothers along with mother Mary, temporarily moved in with Jennie's sister Georgia's family on south Baltimore Street. During the first two days of the battle, Jennie found a way to help the Northern cause by baking bread for and taking water to the Union soldiers fighting in the area.

A few weeks earlier, the 87th Pennsylvania and the 2nd Virginia were among the infantry units opposing each other at the Second Battle of Winchester. The Culp brothers and Skelly were all fighting on the same battlefield. Blessedly, the Culp brothers did not have the misfortune of facing each other on the field. Skelly, however, was not so lucky. He was badly wounded, taken prisoner by the Confederates and laid up in a rebel field hospital. Wesley Culp found Skelly after the battle subsided and visited with him as he was confined to a hospital cot. Jack had written Jennie a letter and asked Wesley to deliver it to her should Culp get to Gettysburg in the following days. Culp stashed the note in his breast pocket and then marched with his regiment to the north.

Wesley Culp did make it to Gettysburg with the Army of Northern Virginia on July 1st, 1863. The Stonewall Brigade encamped east of town in view of Culp's Hill, which was becoming occupied by Union forces. Culp's Hill, along with Cemetery Hill beside it, would, by the following morning, become the extension of the Union's extreme right flank, known as the "Fish-hook." Ironically, Wesley Culp's uncle owned the hill and the farm surrounding it. Wesley, brother Will and Jack Skelly - as young boys and teenagers - explored and hunted on that very hill.

Sometime during the morning of July 2nd, Wesley was deployed on a skirmish line through the woods along Rock Creek. In an exchange of gunfire, in the shadow of Culp's Hill, Wesley Culp was killed - he would never deliver Jack's letter to Jennie. Culp died about a mile or so from Georgia McClellan's house, where Jennie was staying. Wesley Culp was just 24 years old.

A view of Gettysburg from the top of Culp's Hill

The next day, Jennie Wade was up early and began the task of kneading dough to bake bread and biscuits for the Union soldiers. Even though the fighting had already resumed in the streets and bullets could be heard zinging just outside the house, Jennie busied herself. Certainly, she kept preoccupied in the reverie of her betrothed, Jack Skelly. In addition to dreaming about their wedding day, she undoubtedly worried for his well-being. At this point, she had no idea as to where or how he was.

The McClellan house was caught in the crossfire of the fighting in south Gettysburg on the morning of July 3rd. It is believed that the house was peppered with over 150 bullets. The photo on the right is of the north side of the McClellan house. The bullet holes in the door and brick can be plainly seen.

Jennie stood at the kneading table in the house's kitchen preparing bread dough throughout this hail of gunfire. One of the bullets (reportedly the large hole on the right center part of the door with the black stain beneath) passed through this door and another interior door, hit young Jennie in her back and pierced her heart.

She was killed instantly; dead as she fell to the floor. A picture of Jack Skelly (the photo above, actually) was found in her apron pocket. Jennie Wade was the only civilian killed during the Battle of Gettysburg.

On the morning of July 4th, 1863 - Independence Day - as the Army of Northern Virginia began its retreat, Mary Wade baked 15 loaves of bread for the Union soldiers with the dough that her daughter had died preparing the day before.

Jack Skelly languished in that Confederate field hospital for a month. Then, on July 12th, he gave up the ghost and died from his mortal wounds. He was not yet 22 years old when he passed. Young Johnston "Jack" Skelly died unawares that his rebel friend and his fiancee had gone before him.

Epilogue

After July 1st, General Buford's 1st Cavalry was sent to the rear of the front to refit itself. This preeminent division of horsemen would see no more fighting at Gettysburg. Buford had accomplished what he set out to do: delay the advance of the Confederates long enough for the Union to secure the advantageous high grounds. John Buford had unwittingly secured his place in American Military History with his heroic and astute actions on July 1st.

From there, John Buford and his men rode on. A relentless soldier, Buford pushed hard – no one more so than himself. Plain-spoken and serious, the General abhorred politics and pomp; rather, he was a man of focused and determined action. Tragically, General Buford – the first hero of Gettysburg – would not live to see the end of 1863. He literally worked himself to death. On the field only weeks before his premature death of exposure and exhaustion complicated by Typhoid, Buford was only 37 years old when he passed.

President Lincoln, himself, granted a deathbed promotion for John Buford to Major General. Upon learning of his promotion, Buford said, “It is too late, now I wish I could live.” John Buford was laid to rest at the United States Military Academy (West Point), New York.

July 3rd, 1863, went on to become one of the bloodiest, most controversial and definitive days in American military history. General Longstreet’s disagreement with Lee’s approach, and Longstreet’s overall despair of the situation became manifest in his uncharacteristic lack of zeal to execute the battle plan. Ultimately, his read of the situation yielded the results Longstreet had feared…a fruitless waste of life. General Lee always held Longstreet in high regard and Longstreet respected Lee without limit; nevertheless, the dynamic of their relationship and of the entire war was indelibly changed during the first three days of July, 1863.

In addition to prevailing at Gettysburg, the Union also accepted the conditions of the rebels’ surrender at Vicksburg, Mississippi. General U.S. Grant’s Army of Tennessee had roundly defeated the Confederates and, resultantly, set the stage for securing the West in the Union’s favor. Even though the conflict would continue into 1865, the tide of the war shifted mightily on July 3rd, 1863.

Even though General Longstreet led his army through several more significant battles of the Civil War, history has been decidedly hard on Longstreet, while lionizing Lee. Later reviled in the south for his open criticism of some of Lee’s battlefield decision making, becoming a Republican and U.S. Grant supporter, and perceived northern sympathizer, Longstreet lived out his post-bellum life in controversy, and seemed to revel in it.

Against all odds of surviving years of war on the front lines, General James Longstreet lived until 1904 and passed away just six days shy of his 83rd birthday in Gainesville, Georgia.

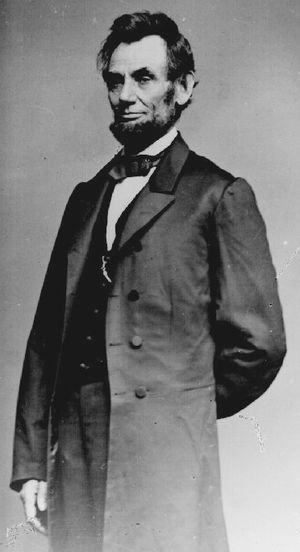

On November 19th, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg for the dedication of the National Soldiers' Cemetery. At this occasion, inspired by the unfathomable sacrifices made on the first days of July earlier that year, he delivered his monumental speech...

The Gettysburg Address

"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom— and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

The Story The Painting The Players Listen & Look

The FOG Blog Store Resources Contact Home