Early on, when I was writing the songs for “The Fields of Gettysburg,” the thematic backdrop of “the field” anchored itself into my thought process. Like a canvas on which to paint the picture, the field is terra firma for the entire piece.

As the title of the project suggests, there are multiple fields at play here. Indeed, the Gettysburg epic was the intersection of a complex matrix of fields, both literal and figurative.

Dictionary.com provides the following definitions of “Field:”

- An expanse of open or cleared ground, especially a piece of land suitable or used for pasture or tillage

- A sphere of activity, interest, etc., especially within a particular business or profession

“Field” is also synonymous with: range, spectrum, realm, theater, and – of course – battlefield.

And, then, there’s the fog - a common natural occurrence that often shrouds the fields of eastern America in the mornings and evenings, obscuring visibility and adding an element of the unknown. During the heat of battle, a phenomenon known as the “fog of war” is almost guaranteed to set in. This kind of fog is generated by an accumulation of incomplete and/or erroneous intelligence about the enemy’s characteristics and movements, unanticipated battlefield dynamics, and the like.

The best laid plans and strategy will quickly erode as the real action ensues, presenting uncertainty (fog) into the situation. Ambiguity pervades the field of war, cloaking the conflict in a strange mist. The leadership, when confronted with the fog of war must read the situation best they can, attempt to anticipate what’s yet unknown, and adapt on the fly. Risk is heightened and the killing field is even more perilous when foggy.

Like much of rural America, Gettysburg is surrounded by an array of fields. A patchwork of properties used in one fashion or another by the land owners. In 1863, most of the fields were parcels of adjacent farms worked by the families that owned the land and partook of the Gettysburg and surrounding towns’ commerce of the day. In this context, the fields of Gettysburg brought forth life and livelihood for those that worked the yield of the land as well as for those who received of the harvest.

It was on and around these fields that the folk of Gettysburg and Adams County raised their families. Not only was much of what would become the classic American work ethic developed in farm communities like Gettysburg around the country at that time; so were generations of Americans who would ultimately spread out across the continental United States and build great cities bustling with commerce of all kinds. Subsequently, the stage was set for the magnificent American nation that would emerge during the course of the 20th century.

In this context, the field yields life, reward, prosperity, and hopefulness for the future.

The brutal irony provided by the great battle in July of 1863, is an extreme example of how the very same field can be turned upside down, yielding a completely converse type of harvest…one of death, penalty, desolation, and despair.

This contrast was not lost on the American people of that time. Surely, the thought that everything the country collectively worked for since before the Revolution was being destroyed by the (Civil) War was ever-present in the mind of the people. Destruction wrought on American fields of plenty, by the middle of 1863, had smothered the mood of the country – a black cloud of despair laid heavy over the nation.

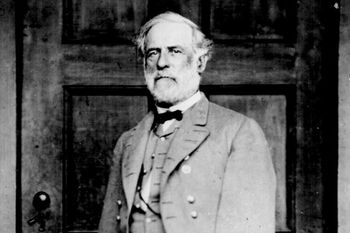

Robert E. Lee aimed to use this dark mood to the Confederacy’s advantage. While President Lincoln and his cabinet struggled to place an effective General-in-Chief at the helm of the Army of the Potomac, Lee was revered on both sides of the conflict. He had honed his Army of Northern Virginia into a sharpened spear. General Lee also carried a lot of stroke amongst the rebel leadership. Confederate President Jefferson Davis was desirous of Lee to mobilize some of his army’s divisions to the west to go to the aid of General Pemberton at Vicksburg, under siege at that time by the Army of Tennessee led by the rising Union star, General Ulysses S. Grant. Lee declined this plea; he believed it more important to concentrate his army and fight their way back into the northern theater.

You see, General Lee wanted to end the war. He wanted the result to be a peaceful coexistence of two countries in place of the one established in 1776. Notably, Lee’s own father was an American patriot who served as an officer under George Washington in the Revolutionary War. “Light Horse Harry” Henry Lee would go on to become the ninth Governor of Virginia and serve as a Virginia Representative in the U.S. Congress.

Robert E. Lee was the eighth of nine children, and youngest son of Governor Henry Lee. Young Robert went on to West Point and was an exemplary cadet. In fact, it is said that Robert E. Lee holds one of the most perfect records of any cadet to have ever passed through West Point. Prior to the Civil War, Lee served in the U.S. Army for 32 years with great distinction. In 1852, within a decade of the War Between the States, Lee served as the Superintendant of West Point. By all accounts, Robert E. Lee was a great American from a great American family.

However, Lee considered himself a Virginian first – even though he was at first not in favor of secession or the dissolution of the United States. In fact, President Lincoln offered Lee a position of commanding officer in the U.S. Army as the hostilities began to develop. Lee declined; the pull from Virginia was too strong. History suggests that Lee reluctantly had to choose. His decision, no doubt, altered the course of U.S. History.

So it was, in the summer of 1863, Lee determined to drive the Army of Northern Virginia back on to Northern turf. His strategy was to draw the Army of the Potomac into the North, and then fight and defeat it there in its own front-yard. Such a defeat, Lee believed, would finally demoralize the Union citizenry to the point of giving in to the idea of two separate countries that could somehow find a way to peacefully coexist. Ironically, this goal of peace – it seems – could only be achieved through massive, violent upheaval and a drenching bloodshed.

Lee envisioned fields of battle in the North. As the majority of his troops were marched behind the Blue Ridge to shield the Army of Northern Virginia’s movements and intentions, General Lee had no idea where this assault would ultimately take place. Certainly it would be in Pennsylvania, and Harrisburg seemed like the logical city to center upon. What Lee didn’t anticipate because of General J.E.B. Stuart’s conspicuous absence from the theater was that the Army of the Potomac had pursued the Confederate movements (on the opposite/eastern side of the Blue Ridge). The Union forces were mustered straight northward through Frederick, Maryland, and into south-central Pennsylvania.

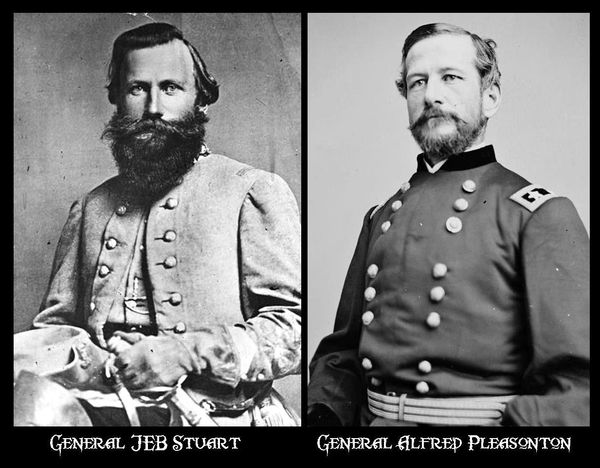

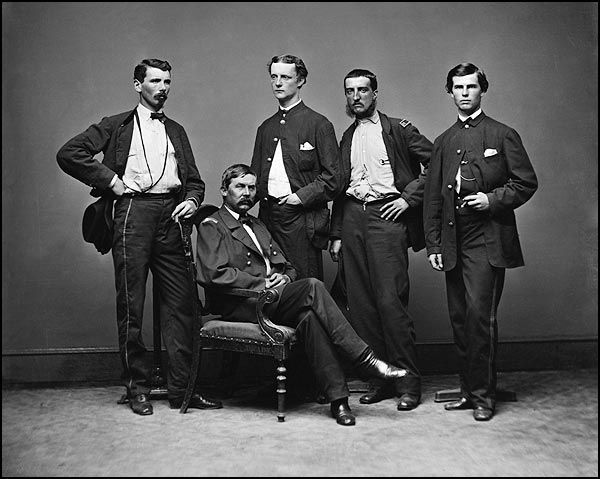

Stuart – a rock star of his day – was Lee’s cavalry commander; the eyes and ears of the army. Stuart had enjoyed a remarkably successful run leading with superb distinction what was regarded as the premier cavalry unit on either side. That reputation was shaken at the Battle of Brandy Station in early June, 1863. Union General Alfred Pleasonton and his cavalry assaulted Stuart’s forces to stave off what Union leadership anticipated to be a raid (by Stuart) on the federal supply lines. One of Pleasonton’s key players at Brandy Station was Brigadier General John Buford, who was quickly proving to be a formidable cavalryman who cast a strong shadow of leadership amongst his troops. While it is generally recorded that the Battle at Brandy Station was essentially a draw, Stuart claimed victory in an attempt to avoid the embarrassment of being taken by Pleasonton’s surprise attack.

Stuart’s cavalry did successfully screen the Army of Northern Virginia’s slip behind the Blue Ridge over the course of the weeks following Brandy Station. But, his planned (and ordered) route to link up with General Ewell’s forces in Pennsylvania was blocked by movement of the Union army. Stuart chose to ride the periphery of the enemy forces, mobilizing far to the east before heading north. Perhaps General Stuart had in mind to obscure the blemish of Brandy Station on his reputation with a grand circumnavigation of the enemy – a tactic he had successfully employed in the past. Whatever drove his decision to campaign as he did prevented him from complying with General Lee’s orders. This disconnection left Lee blind and without reliable intelligence as his entire army marched into unfamiliar, northern territory.

In those days, the army’s cavalry functioned as the scouting and intelligence “branch” – Stuart’s ride deprived Lee of critical battlefield insight prior to engaging the Union army at Gettysburg. Stuart didn’t arrive at Gettysburg until July 2nd, where he was greeted with a harsh rebuke from Lee himself. Conversely, Stuart’s Brandy Station nemesis, John Buford and his division, the Union’s 1st Cavalry, were first on the scene at Gettysburg two days prior. By the time Stuart made it to the fields of Gettysburg, Buford had already redirected the course of destiny with his timely and astute battlefield decision making.

General John Buford & Staff

For General Lee, the Fog of War began settling in.

There were many more factors contributing to the ultimate failure of Lee’s strategy for the Gettysburg Campaign. However, the leadership decision-making and disposition of the cavalry units on both sides of the conflict at Gettysburg had enormous impact on the execution of the battle and the outcome.

Resultantly, Lee’s plan to completely shift public sentiment with a decisive victory on northern turf was not in the cards. In fact, July 4th, 1863 – Independence Day – saw the tide turning hard to the Union side in the wake of both the battles Gettysburg and Vicksburg, which subsided on the very same day on opposite ends of the overall field of the Civil War.

An interesting link regarding the farms & fields of Gettysburg:

http://www.gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/PlacesMenu/Farms.php